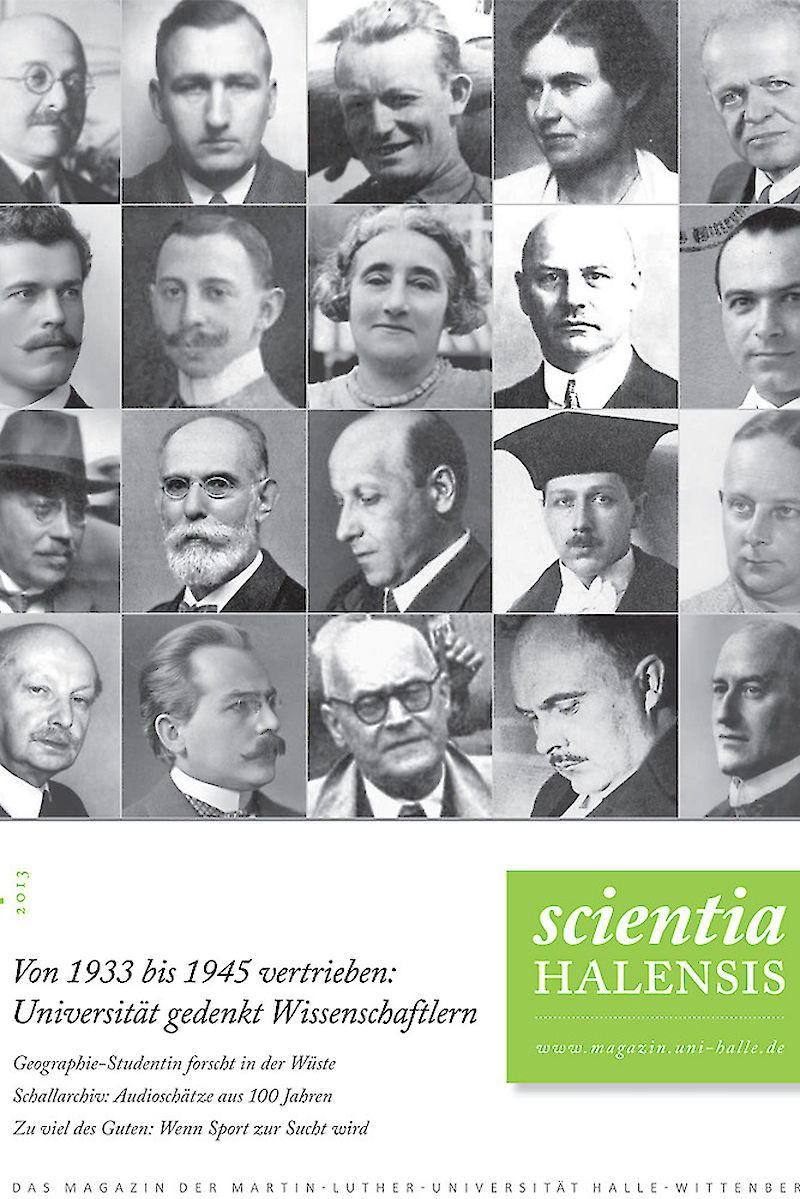

Removed from office, banished from the university

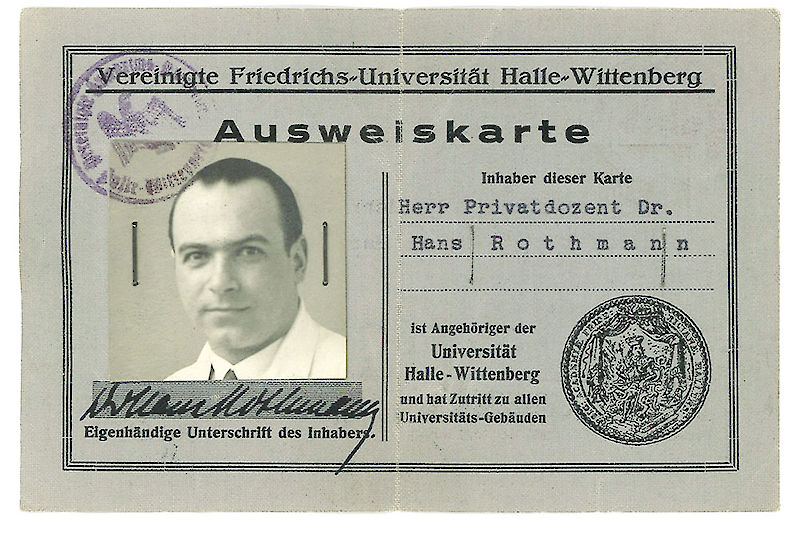

One of these people is Hans Rothmann. Born in 1899, internist, Jew. He came to Halle in 1927 to work as a ward physician at the University Hospital. He was promoted to professor in 1930 and received the Venia Legendi in the area of internal medicine. In May 1933 he was placed on sabbatical and in September the Ministry of Science revoked his teaching licence on the basis of Paragraph 3 of the Professional Civil Service Law, the so-called “Aryan paragraph”. In October he was forced into retirement by decree and in December he no longer received any money. Hans Rothmann was able to emigrate to the US where he could continue working as a physician. He married into a respected Jewish family in San Francisco and had three children. He died there in 1970.

Hans Rothmann’s biography is identical in one point with at least 42 other professors in Halle. They were all suspended from the University of Halle between 1933 and 1945. Today we know of 41 men and two women. Not all of them bore the title of professor. The widely respected Hebrew lector Mojzis Woskin-Nahartabi, murdered in Auschwitz in 1944, and the medical assistant Georg Jacoby, who was forced to leave for “political reasons based on race”, are two examples of the unknown number of employees who were dismissed and students who were expelled.

The project group also included the Pedagogical Academy, founded in 1930 and predecessor of the Pedagogical University, which was integrated into the university in 1933. One example is the biography of the renowned social educationalist Elisabeth Blochmann whose mother was Jewish and who re-obtained a chair in educational science at the University of Marburg in 1952.

The extensive commemorative book, which illustrates these biographies through many photos and documents, takes both a scientific-historical and a personal approach: “We have reinstated these people in the memory of the university,” says Dr. Friedemann Stengel who heads the commission initiated by the university’s rector, Prof. Dr. Udo Sträter. “The university compiled a lot of guilt during the Nazi regime. However it is never too late to research the truth and to face up to the findings and the subsequent responsibility,” Sträter says. Remembering the injustice and the ousted professors is not only necessary, it is also the onset of a further review of history. Friedemann Stengel implemented the project along with campaigners from every area of the university – from jurists to medical scientists and specialists in German studies - as well as colleagues from the German Academy of Sciences Leopoldina in Halle. He and his fellow campaigners worked very consciously to not produce a final list that can be published.

They painstakingly researched individual cases and backgrounds, completed biographies, found descendents and gave back to the former professors their identity and their life history and correlated these to the here and now. An open attitude that calls for further research in the future, but which also enables access to people and their fates.

As in the case of the physician Hans Rothmann. During the course of the project and with help from the Internet, the path his life took could be reconstructed for the first time. Today Friedemann Stengel has contact with his son John F. Rothmann, a well-known political journalist and radio presenter. He provided documents and photos for the project. “We cannot rectify past injustices, but we can and must remember what happened,” says Rothmann. It is not only important to have identified 43 professors, but also to establish contact with their descendents. His father never spoke about the great injustice that befell him.

The book tells the stories that have to be told. Theologian Friedemann Stengel looked closely at the theologian Günther Dehn. He was one of the first professors to fall victim to the Professional Civil Service Law. Dehn was put on sabbatical on 13 April 1933 and let go from the civil service in November. He was forced to leave on the basis of Paragraph 4: for political reasons. Since his appointment in 1931, Dehn, a theologian critical of the church and culture, had been the topic of strong Germany-wide political conflicts. After being suspended from his job at the university, Dehn became a member of the Confessing Church and worked, among other places, at the illegal Church University in Berlin. He was imprisoned between 1941 and 1942 in Berlin. In 1946 he re-obtained a professorship in Bonn. Dehn’s life story is important for the University of Halle because “Dehn’s name was mentioned alongside others at a commemoration ceremony ordered by the provincial government of Saxony-Anhalt and held in the university’s auditorium on 13 September 1947 to remember victims of the Nazi regime,” Stengel says.

Theologian Günther Dehn’s life and re-promotion to professor is one of the project’s points of origin. Friedemann Stengel’s intensive work on the topic turned into the concrete “Ausgeschlossen” project. “It’s unprecedented that so many fellow campaigners could be so quickly found from every area of the university,” he says. “Several had already been working on this and finding very personal avenues.” The scientists could fall back on important material like the intensive examination of the topic within the Faculty of Law, which had commemorated the dismissed jurists with an event and a publication in the 1990s. Another example was the unparalleled collection of material by historian Henrik Eberle “Die Martin-Luther-Universität in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus 1933-1945” [Martin Luther University during the Period of National Socialism 1933-1945] which was published in 2002.

Another supporter of the project has been Prof. Dr. Dr. Gunnar Berg, rector of the University of Halle from 1992 to 1996 and now vice president of the Leopoldina. In 1995 he publicly apologized “with utmost humiliation” for the unlawful de-graduation of scientists by the university between 1993 and 1945 and subsequently until 1990. He applied for the Senate to annul the revocation of academic titles. “Injustice was carried out at the university during two dictatorships. It is responsible for this and must utilise every opportunity to live up to its responsibility,” he says.

John F. Rothmann adds: “What the university is doing is important. I would like my children to know what happened to their grandfather just because he was Jewish. I’d like them to understand that not only was his suspension unlawful, but that the silence of his colleagues at the university and the silence of a generation of Germans played a terrible role in this tragedy.”