Context: Are there too many academics?

I first read the phrase “academic proletariat” in a book by Friedrich Paulsen written at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Even then, there were complaints about “too many” students. This debate has accompanied the development of universities in Germany to the present day. It must have something to do with German culture. Behind this is a fear that “too many” academics will not find work and that this will lead to problematic conditions in society. This probably has something to do with the expectation that anyone who has completed a particular course has to find a job that actually corresponds to it. Behind this is an image that goes back to Lutheran vocational ethics. This debate is unimaginable in other countries.

In Germany, higher education has been expanding, especially since the end of the Second World War: there are more universities, more courses and more students. Politicians were always quite critical of this development until the mid-1990s. This is also due to the fact that we in Germany have an internationally unique dual vocational training system, which is always regarded as the backbone of the German variant of industrial capitalism. This only changed when major international comparative studies showed that Germany’s student rates were relatively poor by international standards.

In 2011, the number of new students reached the number of those starting vocational training in the dual system for the first time. This again was a problem for some politicians. There were even some critical voices from universities: philosophy professor Julian Nida-Rümelin put forward the theory of “over-academisation”, which many others are grappling with again and again. This is surprising because it consequently requires young people to abandon better options in life and access to good opportunities that go hand in hand with studying.

However, the over-academisation argument is not empirically covered. Unemployment statistics for academics show that the unemployment rate over the past ten years has only fluctuated between two and three percent. Other studies show that university graduates are usually placed appropriately in the employment system – in appropriate jobs with adequate pay. A taxi driver with a university degree is not a statistically significant factor.

It is not easy to explain where this balanced situation comes from. In any case, it is not the result of educational planning. Since the 1970s, politicians have been trying in vain to adapt the development of the higher education system to a supposed demand for qualifications, and to direct those entitled to study into those subjects that they consider important for Germany as a business location. This kind of control to access to higher education is only possible in exceptional cases, not least for constitutional reasons.

The situation also does not result from young people basing their choice of subject on future or supposedly expected future conditions for their degrees on the labour market.

The theory is now that the situation is balanced because the world of work is largely adapting to the development of university graduates. You can imagine it like this: as higher education expands, more and more application-orientated courses of study are being established. These usually draw on the theoretical knowledge of various academic disciplines. It is assumed that certain problems in the working world can be solved by what is known as the “application” of this knowledge. Either already existing occupational problems are redefined or new ones are created for which the course graduates are then available as legitimate problem solvers. For example, learning therapy courses are now being established. Pupils’ learning problems are therefore no longer regarded as common pedagogical problems for which teachers are responsible. To a certain degree, they are now regarded as an expression of mental disorders that require diagnosis and therapy. And it is no longer teachers who are responsible for this, but academically trained learning therapists. This can also be applied to other courses. Osnabrück University of Applied Sciences, for example, offers a course in “sustainable turfgrass management”. There is obviously an opinion that generalised practical knowledge is no longer sufficient to care for grass in a reasonable way. And I’m telling you: after a short time, the first large football clubs and golf clubs hired academically trained turf managers. Because the mere practical knowledge of a conventional groundsman appears to have been devalued with the establishment of university courses.

Of course, an academic qualification does not necessarily mean that problems in the working world can be solved better or more appropriately. This is the case in some areas. These are often areas for which techniques can be developed, i.e. simplifications that work and that can work with isolated links between cause and effect.

But there are many areas in which this doesn’t work. For example, no pedagogical model helps you to cope with a current situation in dealing with children. The interesting thing is that the courses that are expanding are the ones that have to do with areas of action that are largely beyond the reach of technology: social professions, management, etc., and where it is therefore highly uncertain whether and how academic knowledge can be implemented in professional action.

This article appeared in print as part of the series "Context", in which researchers of Martin Luther University explain recent topics in their respective fields, providing background and contextual information.

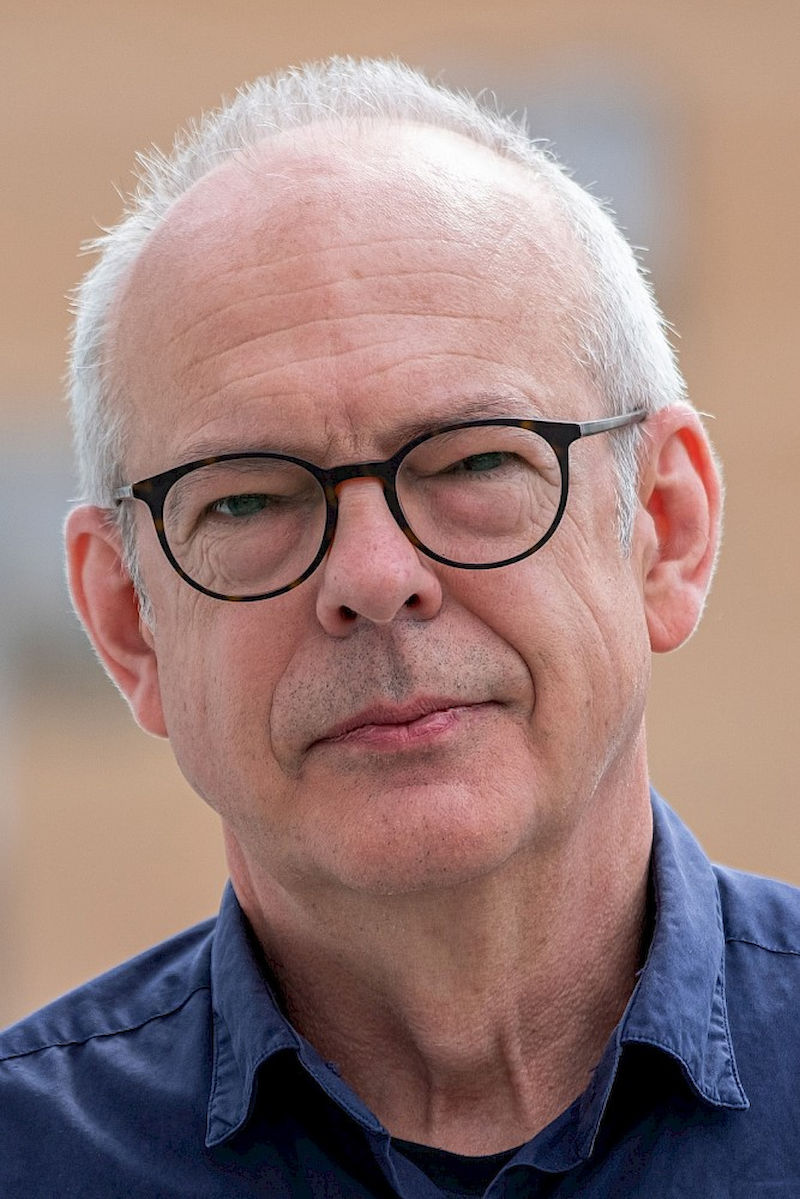

Professor Manfred Stock has been Professor of Sociology of Education at MLU since 2014. He is currently leading two major research projects on the development of academic study programmes and the academisation of employment.

Contact:

Professor Manfred Stock

Institute of Sociology / Sociology of Education

Telephone +49 345 55-24240

Mail: manfred.stock@soziologie.uni-halle.de

Kommentare

Krepper am 02.06.2025 20:19

Ich finde, dass die Ausfuehrungen von Nida Ruemelin tatsaechlich empirisch belegt und nicht falsch, sondern richtungsweisend sind. Die berufliche Bildung hat Wert. Das sehe ich bei zu spezifischen Bachelorstudiengaengen leider nicht so deutlich.

Reply