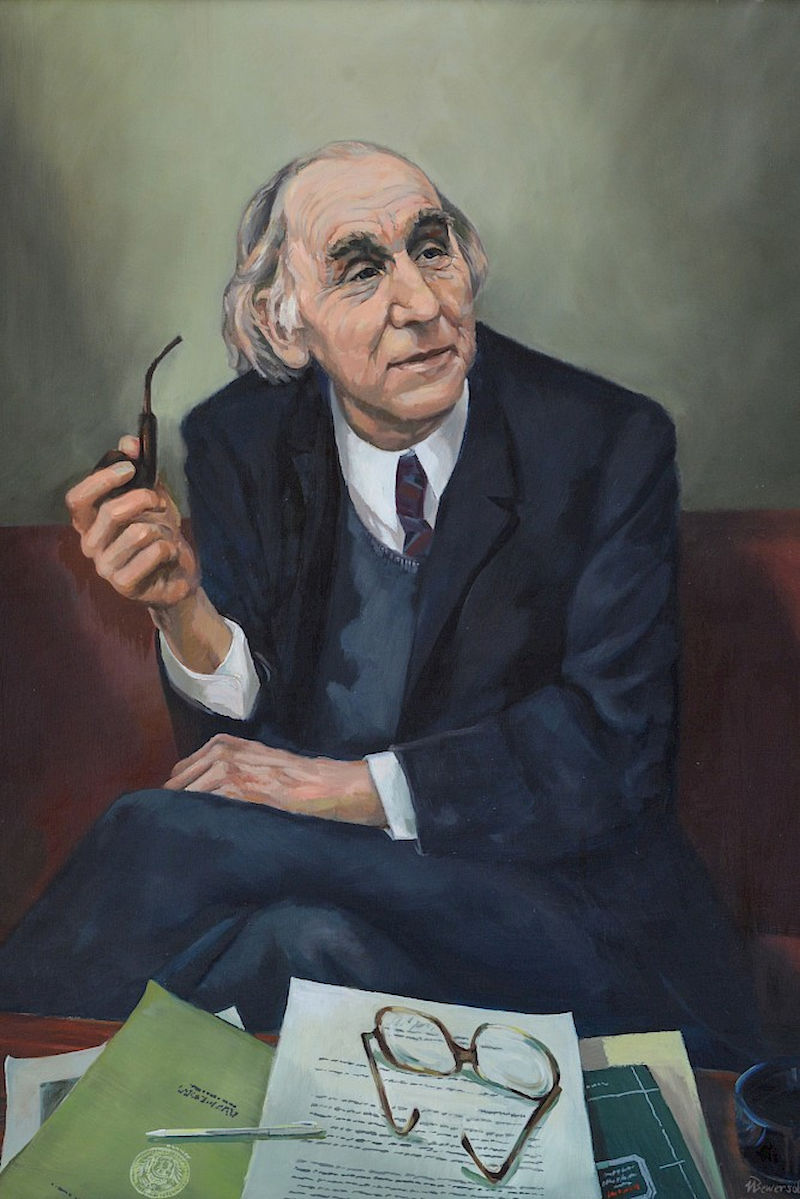

Big Names: Heinz Bethge

Heinz Bethge designed the first electron microscope in Halle in the early 1950s. A short time later it was built in the institute’s own workshop and went into operation in 1952. Back then, Bethge believed that this imaging technique could be utilised in solid-state physics. He presented the initial findings of his work in 1958 at an international conference for electron microscopy in Berlin. This caused a stir among experts as well as political decision-makers, and led to the decision to establish a central research centre for electron microscopy on the Weinberg located at the time at the edge of Halle.

Bethge, then just 40 years old, and his young team started building the facility in 1960. Conditions at the start were modest with the young scientists initially having to conduct research in the rooms of a former restaurant. They shared a former dance hall at the institution with a student cafeteria. What started out as being more or less provisional, led to the founding of the Institute for Solid State Physics and Electron Microscopy (IFE) in 1968 - an institution which, under his leadership, finally helped Bethge achieve international renown.

Countering interference

Heinz Bethge would have turned 100 in November. He died in 2001, but the Magdeburg-born son of a master carpenter was already a well-known figure during his lifetime. He was recognised worldwide in his field, was easily approachable, and had a personality that enabled him to stand up to the politically powerful in the GDR. At MLU, where he had held a professorship in experimental physics since 1960, he supported students who were politically persecuted.

In 1974 Bethge was elected XXIII.President of the National Academy of Sciences Leopoldina. Germany’s oldest and very distinguished scholarly institution was able to steer free of political interference in GDR times largely due his efforts and those of his predecessor Kurt Mothes. Time and again the state attempted to weaken the independence of science.

For example, in the early 1980s, the SED called for the Leopoldina to accept more party members. Bethge rejected this request due to his deeply held conviction that membership should be based solely on scientific excellence.

His resistance was both successful and fraught with consequences. Just how much so, is recounted by older employees of the Leopoldina: The party retaliated for the independence of the scientists and barred the Leopoldina from using a lecture hall at MLU that it urgently needed for events. This was a situation that Bethge could not and would not accept.

He made use of his good contacts and international networks by turning to Berthold Beitz for help. At the time, Beitz was the chief representative of the Krupp Foundation in the Federal Republic of Germany. It was a highly unusual move and allowed him to obtain enormous financial resources for the construction of the Leopoldina’s own lecture hall. The money donated from the West was converted to East German marks through the help of the Special Department for Commercial Coordination at the Ministry of Foreign Trade of the GDR (KoKo) headed by Alexander Schalck-Golodkowski.

And so, a new lecture space was constructed at Emil-Abderhalden-Strasse 36 with the help of the “class enemy”. Bethge himself, it is said, brought the tiles for the new building with him from his travels to the West and later, at the building’s inauguration in 1989, even tapped the beer himself during the festivities.

Renowned guests

Under his leadership, the Leopoldina acted as a “hole in the wall” and proved vital for research exchanges in the Eastern Bloc countries. The big names in the scientific community regularly came to the annual conferences in Halle, located in sealed-off East Germany. Among the guests were renowned scientists from all over the world, including the German-American and Nobel laureate Max Delbrück and the physicist Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, brother of Richard von Weizsäcker, a politician and the President of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Bethge lived to see the merging of science after the fall of the Berlin Wall. In 1992, from the Institute for Solid State Physics and Electron Microscopy, which he headed until 1985, two top-notch research institutes emerged: Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Microstructure Physics, which was the first MPI in the new German states, and the today’s Fraunhofer Institute for Microstructure of Materials and Systems IMWS. In the same year, Heinz Bethge was awarded the Great Cross with Star of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany. He was one of the first citizens of the former GDR to receive this honour.

Big Names

The University’s history connects it to many well-known figures or big ideas. Not everyone, however, is fully clued up on the whys and wherefores of these connections. But that’s about to change. The section, “Big Names” is a reminder of the outstanding researchers and academics who have links to the City of Halle.