The mummy’s colourful clothes

Work began in August 2013. The project focuses on finds from the autonomous Uighur region in Xinjiang which is located in the north-west region of today’s People’s Republic of China. These are mostly complete burials of clothed mummies, some of which were found ten years ago and then taken to various museums and institutions in Xinjiang. The good condition of the organic material, some of which is excellently preserved, is attributed to the extremely dry climate. “Microbiological, chemical and photochemical processes cause natural ageing processes and can also subsequently change the colour,” says Csuk.

This evidence is of major importance for research into the life of the inhabitants of Eastern Central Asia between 1,000 BC and 300 AD. It contributes to our understanding of the early bridges between Asia and Europe, Csuk goes on to say. It’s about what clothes reveal about a society and its history. Dyed clothing fulfils a specific purpose: it reveals to us something about the wearer and thereby represents a means of communication.

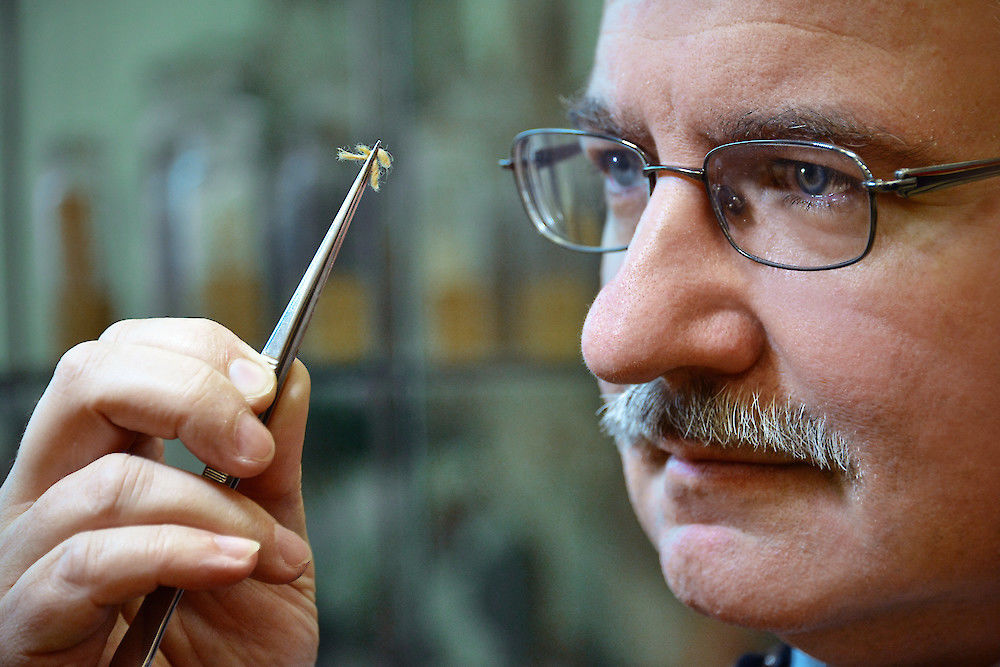

The project is investigating a total of around twenty complete burials which contain clothing, skirts, cloaks, face veils, shoes and bags. Initial trials are currently underway which use tiny samples to determine the dye and the type of animal whose wool or skin was made into the garment. “We hope to be able to make detailed statements on the age of the finds, the raw materials, dyeing techniques, processing and manufacturing processes that were used, and to make statements on aspects of a possible technology and raw material transfer,” Csuk explains.

“We already know that organic natural dyes are usually obtained from various plant-based and animal-based raw material sources and that different dyeing processes were used,” Csuk explains. Stains, vat dyes and direct dyes were used among other things. For example analyses of dyes used in prehistoric textiles have shown that red colouring is usually obtained from the so-called anthraquinone class of dyes which can be isolated in the Rubiaceae family or in various scale insects. The vat dye indigo was usually used for the colour blue.

The chemists can take advantage of the knowledge that has been obtained by analysing the dyes used in the clothing of the Empress Edith from the Magdeburg Cathedral. Together with the Museum of Prehistory they were able to determine that a red kermes dye, obtained from the kermes insect, was used to dye the monarch’s last silk cloak.

“We use state-of-the-art methods of instrument analysis and trace analysis,” says Csuk. The non-destructive methods include a look through the scanning electron microscope and special spectroscopic methods. In the case of invasive methods, in other words fabric damaging methods, the dye is separated - or extracted - from the thread using a suitable solvent. This is followed by an intricate analysis of the extracts. Various mass spectrometric methods are used until clear findings are obtained.

The sub-project in Halle is part of the BMBF project “Silk Road Fashion: Clothes as a means of communication in the 1st millennium BC, Eastern Central Asia”. The project is being managed by the German Archaeological Institute (DAI) in Berlin. Also participating in the project are two Chinese research groups, a team from Freie Universität Berlin, the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy of Science and Humanities and the State Office of Heritage Management and Archaeology Saxony-Anhalt – Museum of Prehistory.

The project will end on a special note in 2017: the historical clothing of ancient cultures will be presented at an international fashion show. On display will be the material, colour and cut of authentically reproduced garments.